A Brief History of Chinese Embroidery

Complete Browse Page

1. Origin—in Remote Antiquity

A silk embroidered belt of the Warring States Period preserved in Jingzhou Museum, Hubei Province.

1. Origin—in Remote Antiquity

It is very difficult for us to ascertain the time and place for the birth of embroidery in Chinese antiquity. However, there is no doubt that it originated from the era when human textile and sewing were born. The earliest embroidery started from tattooing, which was later turned into handcraftsmanship applied to garment decoration in close combination with practical and attractive decoration in daily life. It was the beginning of the change from backward facial tattooing to civilization and progress of human beings. A bone needle unearthed from the Upper Cave Man Site in Zhoukoudian in Beijing dates back 8,000 years. It is 8.2 centimeters long, with the widest part being 0.33 centimeters in diameter. So far, it is the earliest sewing tool known in the world (FIG. 9). One can imagine that when the processing of needles, threads, and fabrics was available, it was natural for the emergence of products for sewing and embroidery.

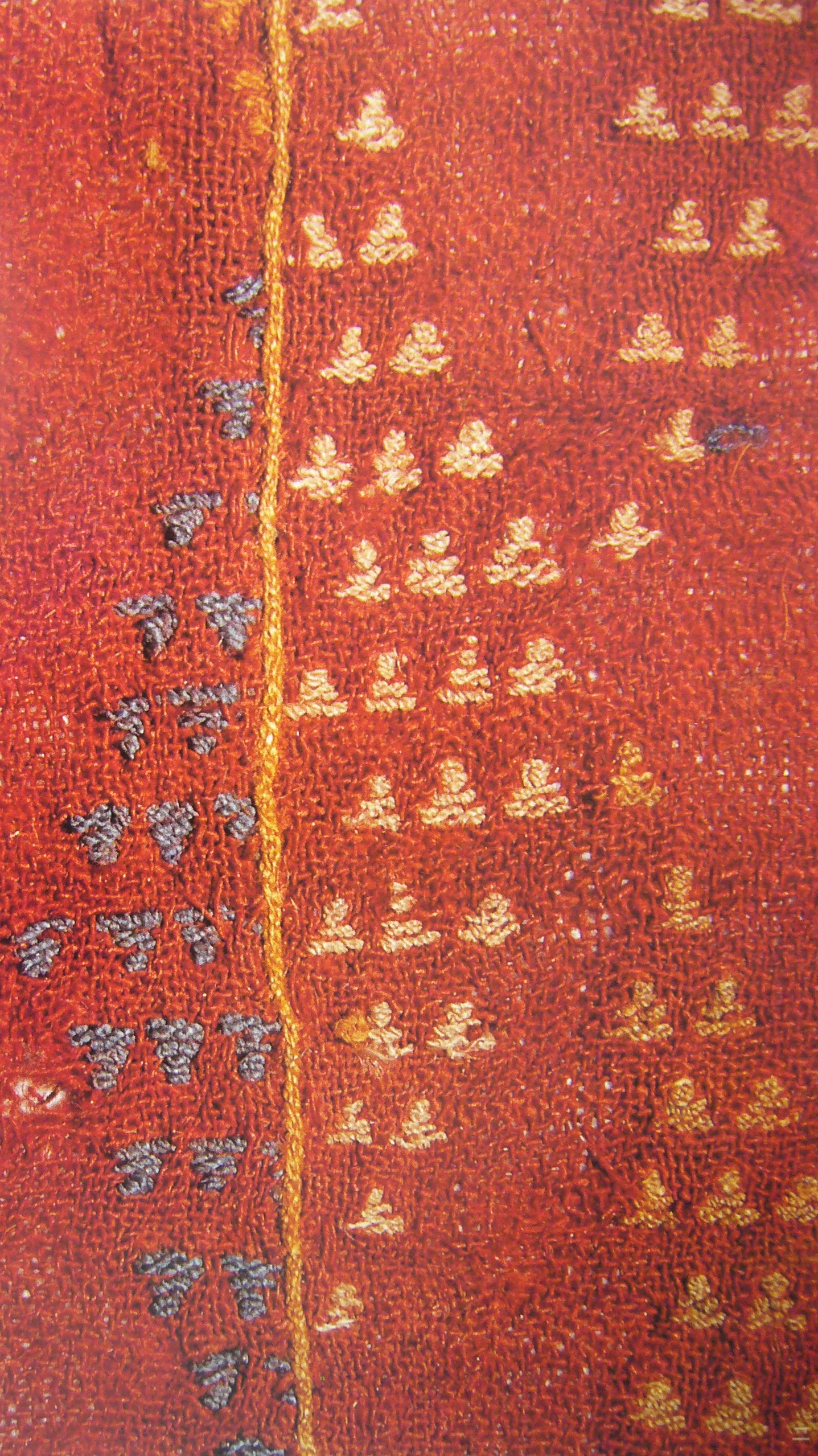

Prior to the emergence of cotton and linen fabrics, our predecessors in antiquity resorted to leather tanning for clothes. They brought about patterns on leather clothes by using bone needles to sew leather stripes or plant fibers, which was closer to the habit of tattooing. Before accurate excavated objects can be used as evidence, we can deduce that prior to the emergence of fabric, application of embroidery onto leather may be more frequently seen. A leather belt embroidered with silk that was unearthed from Tianxingguan Tomb in Hubei Province in 1978 may serve as evidence of this deduction. It is 40 centimeters long and 7 centimeters wide. The leather is covered with a layer of silk tabby embroidered with brown and dark yellow silk-threaded circling hornless dragon (chi) patterns. The top and the bottom are embroidered with horizontal S-shaped patterns (FIG.10).

FIG. 9 A sketch map of the bone needle as used by the Upper Cave Man at Zhoukoudian in Beijing.

FIG. 10 A silk embroidered belt of the Warring States Period preserved in Jingzhou Museum, Hubei Province.

2. Early Emergence—the Western Zhou Period (1046–771 BC)

Traces of chain stitch on a silt of the Western Zhou Dynasty preserved in Baoji Museum, Shaanxi Province.

2. Early Emergence—the Western Zhou Period (1046–771 BC)

Early Emergence—the Western Zhou Period (1046–771 BC) Based on present archaeological excavations, the immature dyeing techniques at the time did not make it possible for color to be applied to threads before stitching. Instead, color was applied after the embroidered patterns were finished. Let’s take a look at the marks of silk fabric with patterns embroidered in chain stitch from the Western Zhou Period that was found in the mud in the Tomb of Yubo in Baoji, Shaanxi Province in 1974. With this kind of embroidery, patterns were first outlined by yellow silk threads on the dyed silk fabric and then big patches of color were smeared and dyed on the embroidered patterns, including such colors as red (natural cinnabar) and yellow (realgar), etc. This was the feature of embroidery in its early period of development (FIG.11). Fabrics used for embroidery in this period did not have close-knit fibers. Therefore, patterns embroidered were sparser than those in the following generation. It was even more evident if the fabrics were cotton, linen, and wool. For instance, in 1978, a piece of woolen embroidery from the Western Zhou Period unearthed from the Ancient Cemetery Area in Wubao, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is marked by a reddish brown wool with plain woven fabrics structured with the same warp and weft. Gorgeous geometric patterns in small triangles were embroidered with running stitch by white wool threads as well as threads dyed in yellow, blue, and pale green. When unearthed, they were seen over the body of a dead female. So far, it is the earliest embroidered object (FIG.12).

FIG. 11 Traces of chain stitch on a silt of the Western Zhou Dynasty preserved in Baoji Museum, Shaanxi Province.

FIG. 12 Woolen embroidery with running stitch of the Western Zhou Dynasty preserved in the Museum of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

3. Taking Form—the Spring and Autumn Period, the Warring States Period, the Qin and the Han Periods (770 BC–220 AD)

The most representative embroidery in ancient China was none other than chain stitch between the Warring States Period and the Han Dynasty. Despite its mono-needlework and unchanged craftsmanship, its needlework was neat and unrestrained, its patterns were spirited and regularly laid out with changes in symmetric distribution and interaction amidst smoothness. Such features can be found in many embroidered articles unearthed in the same period. Phoenix was regarded as a mythological bird in remote antiquity in China. Therefore, it was frequently seen on embroidered patterns at that time. Its flowing posture is varied, full of rhythm as well as miraculous and illusive appeal, revealing the appeal of aesthetics and the style of romanticism of the culture of the Chu state in the Warring States Period. For instance, the phoenix in this embroidered article is marked by a high crown, expansive wings, lowering head at one end of the wing, and slightly curved feet, seemingly flying in the air or coming back from the fairyland in romantic conception and gorgeous colors. The entire article was produced with chain stitch, meticulous, and proficient needlework without any trace of stiffness, showing superb embroidery needlework of folk artists more than 2,000 years ago.

3. Taking Form—the Spring and Autumn Period, the Warring States Period, the Qin and the Han Periods (770 BC–220 AD)

During the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period (770–221 BC), embroidery was brought about by single chain stitch needlework. The most representative was a batch of embroidery in the middle and late stage of the Warring States Period (475–221BC) that was unearthed from Chu State Tombs of Jiangling County, Hubei Province. Though buried underground for over 2,000 years, they still appear gorgeous with exquisite patterns and vivid styles. They are well preserved in big numbers featured by delicate and mature skills of embroidery. There are mostly over ten kinds of colors, i.e. brown, reddish brown, dark brown, eosin, vermilion, orange-red, golden yellow, earthen yellow, yellowish-green, dark green, blue, and grey, etc. Each pattern is combined with three to five kinds of colors that are mainly in warm hues in sharp contrast. Patterns are chiefly marked by dragons, phoenixes, tigers, and flowers. These different patterns look beautiful, neat, unrestrained, vivid, and regularly laid out with changes in symmetrical distribution and interaction in smoothness (FIGS. 13).

The development of embroidery benefited from the unification of different states in China in the Qin Period and the Han Period (221 BC–220 AD) when the system of conferment was replaced by the system of centralism. Economic and cultural exchanges and integration became increasingly extensive. Social and agricultural production as well as handicraft production became increasingly prosperous. The textile industry developed rapidly, leading to the emergence of professional embroiderers. Apart from silk embroidery, embroidery on woolen products is also often seen among embroidered articles unearthed in north-west China. Motifs of embroidered patterns became richer. In addition to mature chain stitch, short running stitch, blanket stitch and bead work also began to appear. They were new embroidery technique used to try to combine patterns. The development of mineral dyestuff and application of plant dyestuff further expanded the color spectrum of threads for embroidery.

Embroidery is of practical use, but it is not only confined to the garment since it has begun to be associated with daily decorative articles, such as sachets, gloves, pillow-towels, needle-thread containers, parcels with lace trimmings, brocade robes, knee-pads, suspenders, face powder bags (FIG. 14), mirror bags, vamps, ribbons, and embroidered trousers, etc. As an important turning point in the history of embroidery, it laid the foundation for the enhancement of the artistry of embroidery in the following generations. What deserves to be stressed is that representative patterns of embroidery appeared in the Qin Period and the Han Period, i.e. embroidery with swallow motif and embroidery with auspicious cloud motif. As terms of embroidery, the two patterns were seen in literature at that time, showing that the popularity and professionalism of embroidery were quite well-grounded.

FIG. 13 B Embroidery of Phoenix Patterns Warring States Period The most representative embroidery in ancient China was none other than chain stitch between the Warring States Period and the Han Dynasty. Despite its mono-needlework and unchanged craftsmanship, its needlework was neat and unrestrained, its patterns were spirited and regularly laid out with changes in symmetric distribution and interaction amidst smoothness. Such features can be found in many embroidered articles unearthed in the same period. Phoenix was regarded as a mythological bird in remote antiquity in China. Therefore, it was frequently seen on embroidered patterns at that time. Its flowing posture is varied, full of rhythm as well as miraculous and illusive appeal, revealing the appeal of aesthetics and the style of romanticism of the culture of the Chu state in the Warring States Period. For instance, the phoenix in this embroidered article is marked by a high crown, expansive wings, lowering head at one end of the wing, and slightly curved feet, seemingly flying in the air or coming back from the fairyland in romantic conception and gorgeous colors. The entire article was produced with chain stitch, meticulous, and proficient needlework without any trace of stiffness, showing superb embroidery needlework of folk artists more than 2,000 years ago.

FIG. 14 An embroidered face powder bag with cloud patterns from the Eastern Han Dynasty preserved in the Museum of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

4. Maturity—the Southern and Northern Dynasties, the Sui Dynasty, and the Tang Dynasty (420–907)

FIG. 15 Colorful Embroidery of Supporters of Buddha Statues Southern and Northern Dynasties Supporters are referred to as patrons in Buddhist activities. Anyone who invests in building Buddhist grottos and offers sacrifice to Buddha statues can have his image painted or embroidered under Buddha statues as a benefactor. This embroidered article is preserved in Dunhuang Research Institute, Gansu Province.

4. Maturity—the Southern and Northern Dynasties, the Sui Dynasty, and the Tang Dynasty (420–907)

What about embroidery in the Southern and Northern Dynasties? The answer is in the colorful decorative embroideries on the supporters of Buddha statues that were discovered in the Dunhuang Mogao Grottos in Gansu Province in the 1960s. Buddhism was popular in the Southern and Northern Dynasties. Naturally, more religious objects were decorated by the craftsmanship of embroidery (FIGS. 15). Although the same chain stitch needlework was applied to some articles of embroidery in the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534), the rise, rhythm, and exquisiteness in animal-shaped patterns were still pervasive. The content of these patterns were added with elements of decoration and artistic paintings. Depiction of human figures in Buddhist embroidery was accurate in detail, making all creatures in Mother Nature vivid, including birds, dragons, flowers, grass, trees, and fruits. The design of craftsmanship was exceptionally artistic just like a picture with emotion and sceneries, showing that the artists already had the innovative awareness of changing embroidery for practical use to embroidery for appreciation.

The prosperity of the Sui Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty ushered in the continuous development of Chinese embroidery. Extensive emergence of religious embroidery marked by embroidered scriptures and embroidered Buddhist paintings stimulated the vigorous progress of embroidery craftsmanship. In this period, chain stitch needlework of embroidery lost its leading position. From the embroidered articles of the Tang Dynasty, we have found bead work (FIG. 16), straight satin stitch, gold thread couching stitch, etc. Thus, there was more expression in embroidery in the Tang Dynasty (FIG. 17). Embroidered garments and bags and kasaya (FIG. 18) of the Tang Dynasty collected in British Museum are witness to gorgeous and novel needlework of the Tang embroidery. Petals on the Tang kasaya were embroidered with a feathering-like effect, making the picture more vivid, three-dimensional, elegant, and eye-catching while expanding the use of threads. Having completely changed the forms and modes in patterns prior to the Tang Dynasty, this laid the foundation for the development of realism of embroidery in the Song Dynasty.

FIG. 15 Colorful Embroidery of Supporters of Buddha Statues Southern and Northern Dynasties Supporters are referred to as patrons in Buddhist activities. Anyone who invests in building Buddhist grottos and offers sacrifice to Buddha statues can have his image painted or embroidered under Buddha statues as a benefactor. This embroidered article is preserved in Dunhuang Research Institute, Gansu Province.

FIG. 16 A remaining piece of bead work embroidery in the Tang Dynasty preserved in the Administration Office of Cultural Relics, Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

FIG. 17 Mandarin Ducks and Peonies (Detail) Embroidery on Dark Yellow Twill Damask Tang Dynasty Discovered in the Thousand Buddha Caves of Dunhuang, embroidery on this plain color twill damask with indistinct flowers of the Tang Dynasty is marked by bright colors, a variety of needlework, and novel patterns. Entwining peony was turned out by gold thread couching stitch to reinforce the sense of stereoscope. Vivid and lovely little birds flying across flowers were brought about by gold thread couching stitch for patterns. Flowers and leaves were embroidered in green of different grades by running stitch. Outlines of leaf-stems and leaves were all decorated by simple couching stitch, hence giving prominence to patterns, both decorative and realistic. In embroidered works of flower patterns from the Tang Dynasty, flower postures and structure of branches and leaves were mostly rather stiff, lacking the contrast between yin and yang. However, this embroidered article is featured by rich layers of color-matching on flowers, color-change of different grades on leaves, elegant curved branches, gorgeous tints, and changeable needlework, hence making itself one of the highest quality among all embroidered articles from the Tang Dynasty.

FIG. 18 A kasaya from the Tang Dynasty unearthed in Thousand Buddha Caves of Dunhuang, now preserved in the British Museum.

5. The Prime Period—the Song Dynasty (960–1279)

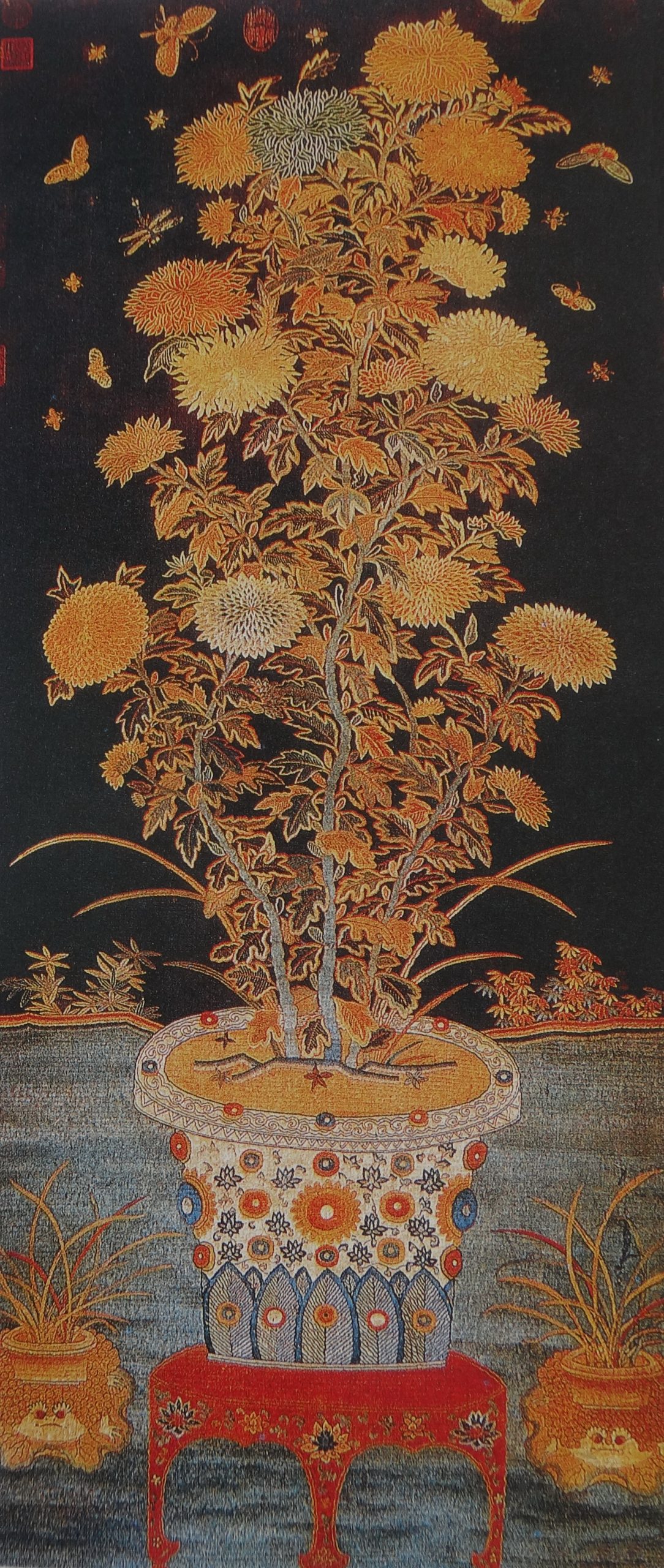

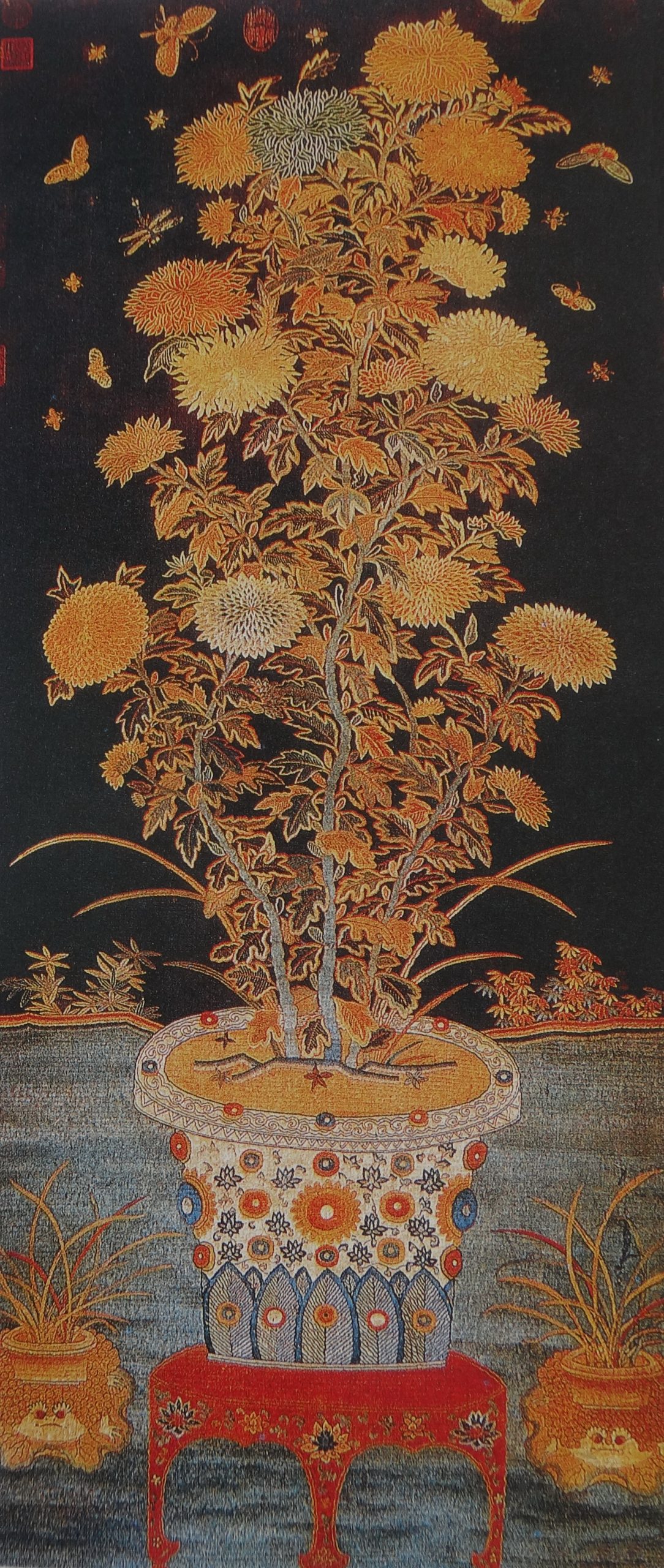

FIG. 19 Chrysanthemum Song Dynasty Embroidery This embroidered article is characterized by chrysanthemums in full blossom, flying butterflies, dragon flies, and bees. Colorful thread-matching is gorgeous and elegant, showing exquisite craftsmanship of embroidery in the Song Dynasty. It is now preserved in the Palace Museum, Taipei.

5. The Prime Period—the Song Dynasty (960–1279)

The Song Dynasty was the cradle for the birth of artistic embroidery, exerting a far-reaching influence on the development of Chinese embroidery. Its art is still highly respected (FIG. 19, 20). Artistic embroidery benefited from the promotion of paintings in the Song Dynasty in which the royal court witnessed a batch of outstanding painters. Their art, if perceived according to the view in contemporary times, is still glorious and incomparable in terms of achievements. In addition, the royal family of the Song Dynasty exerted unified management over the production of embroidery, having set up Directorate for Imperial Manufactories, Crafts Institute, Embroidery Office, Ornaments Office, Silk Brocade Workshop, and Palace Weaving and Dyeing Office, providing favorable objective conditions for the maturity of artistic embroidery. Particularly under the reign of Emperor Zhao Ji in the Song Dynasty (1100–1126), an Embroidered Painting Specialty was established in Imperial Academy of Painting. Embroiderers of this specialty all used works of academy painters to create embroidery. Since the art of calligraphy and painting in the Song Dynasty provided plentiful painting-sketches for embroidery, artistic embroidery developed rapidly. An unprecedentedly high starting point gave rise to the vigorous development of embroidery art in the Song Dynasty. A number of artistic embroidery in the Song Dynasty all took the brushwork, lines, colors, and spiritual appeal of the Song paintings as standards of art, even over striding paintings. They brought the Song embroidery to the peak of amazing vividness and formed embroidery for appreciation independent of previous kinds, such as Plum-Flower, Bamboo and Parrot, White Eagle (FIG. 21), Riding Crane to Yaotai, Okra and Butterflies, and Hibiscus and Crab (FIG. 22).

After that, artistic embroidery advanced ahead as a late-comer and progressed together with embroidery for practical use with a long history, greatly expanding the space for the survival and development of embroidery, led the style of embroidery creation by many noted embroiderers and the growth of various schools of embroidery, enabling the art of Chinese embroidery to enter a new period.

FIG. 19 Chrysanthemum Song Dynasty Embroidery This embroidered article is characterized by chrysanthemums in full blossom, flying butterflies, dragon flies, and bees. Colorful thread-matching is gorgeous and elegant, showing exquisite craftsmanship of embroidery in the Song Dynasty. It is now preserved in the Palace Museum, Taipei.

FIG. 20 Majestic Eagle Song Dynasty Embroidery Its high-rising head, firm chests, and forceful claws were well embroidered. Despite the fall-off of lots of threads due to a long period of time, the eagle still maintains its majesty. This is obviously closely associated with superb techniques of the embroiderer. In spite of extremely fine strands divided and exquisite needlework for feathers, the eagle looks fierce and firm all the same. There were more kinds of innovative needlework for application, showing that embroidery in the Song Dynasty reached art height of immense realism. The eagle was a painting theme favored by scholars in their painting in the Song Dynasty. Versatile Zhao Ji, emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty, was not only good at handwriting, but also at painting flowers, bamboos, feathers, and flowers in water-ink. His Imperial Eagle was detailed and unrestrained in depiction, fully revealing its majesty and fierceness without any roughness and wildness. This embroidered article bears strong resemblance to the spirit of Zhao Ji’s Imperial Eagle.

FIG. 21 White Eagle Song Dynasty Embroidery The eagle was used as part of the garment of warriors in the Tang Dynasty and often compared to a hero. It was quite popular in the Song Dynasty, Liao Dynasty, Jin Dynasty, and Yuan Dynasty. This embroidered article is now preserved in the Palace Museum, Taipei.

FIG. 22 Hibiscus and Crab Song Dynasty Embroidery This embroidered article was imitation of a painting by Huang Quan (?–965), who was a painter in the imperial court of the Western Shu Dynasty. Most of his paintings were associated with unique birds and famous flowers in the imperial court, showing meticulousness, splendidness, wealth, and nobility. Hibiscus and Crabs is now preserved in the Palace Museum, Taipei.

6. Carrying Forward the Cause and Forging Ahead into Future—the Yuan Dynasty and the Ming Dynasty (1271–1644)

.jpg)

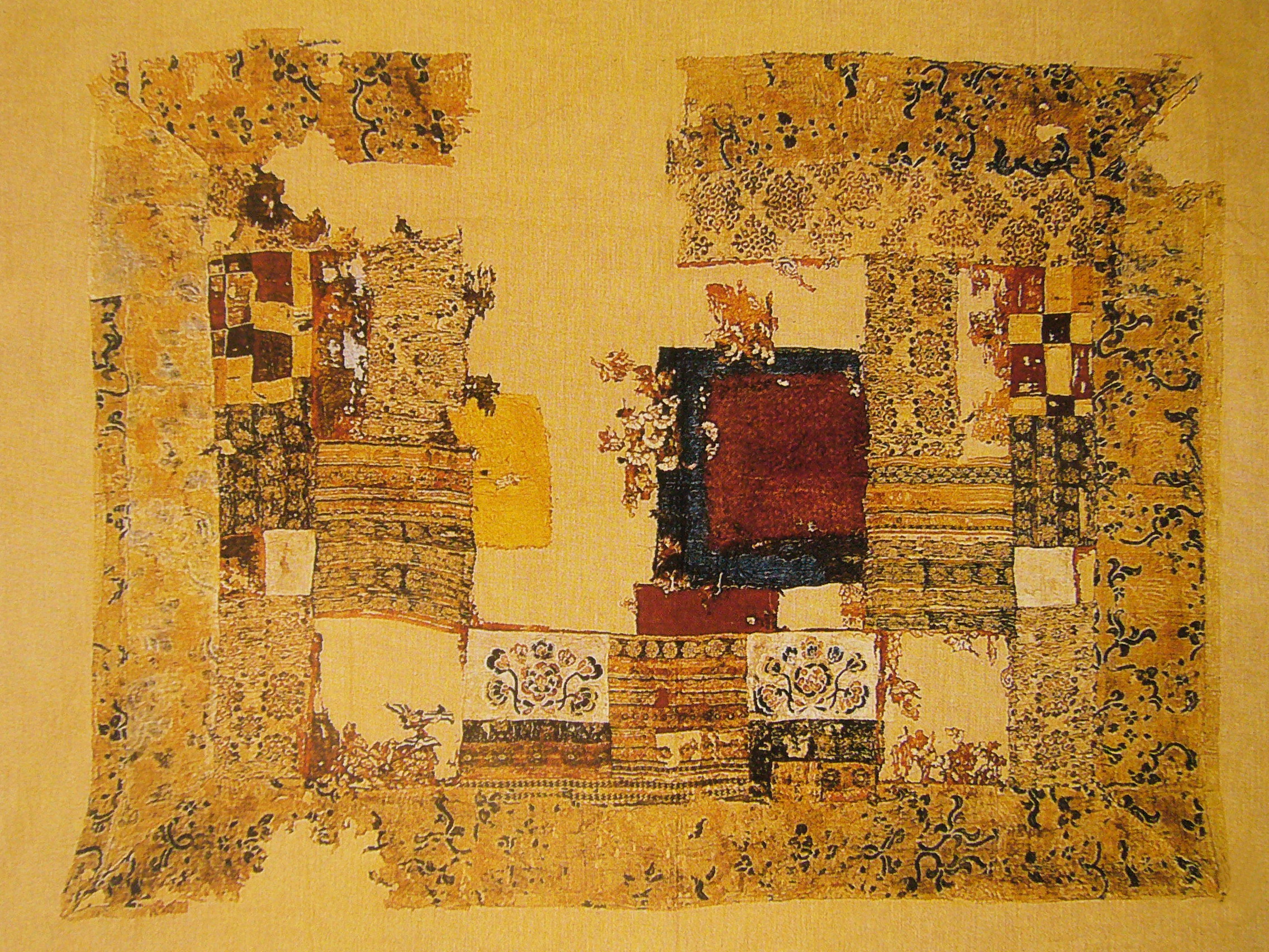

FIG. 23 B An Embroidered Pad of Flower Patterns Yuan Dynasty Needlework for the lotus flowers, lotus leaves, white geese, and butterflies on the surface is ordinary, except that the triangle decorative fringes around are quite special. This kind of needlework is similar to fishing-net stitch. Therefore, it is called fishing-net embroidery. This embroidered article is now preserved in the Museum of Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region.

6. Carrying Forward the Cause and Forging Ahead into Future—the Yuan Dynasty and the Ming Dynasty (1271–1644)

As discovered in the many years of embroidery research of the Yuan Dynasty, there was a kind of unique fishing-net embroidery which is rarely seen and known in the following generations. It is evidence of dividing history into dynastic periods for appraising and appreciating ancient embroidery, having a far-reaching significance on studying and perceiving embroidery in the Yuan Dynasty (FIG. 23).

There were no schools of embroidery to speak of in the Ming Dynasty, only with Gu-Style Embroidery (gu xiu, embroidery in southern China) and Shandong Embroidery (lu xiu, embroidery in northern China) as representatives.

Shandong Embroidery inherited relatively rough and uninhibited features of embroidery for appreciation in the Yuan Dynasty and used double-ply threads. In most cases, a whole thread was used for embroidery. The layout was natural and vivid thanks to direct application of bright colors and the characteristics of freedom and dignity, hence becoming the best among all kinds of embroidery in northern China. Long-standing and classic works of Shandong Embroidery are none other than Hibiscus and Two Ducks and Mandarin Ducks amidst the Lotus Pond, etc.

Gu-Style Embroidery inherited the delicate application of silk embodied in the embroidered calligraphy and paintings of Song Dynasty embroidery, marked by the application of soft and tender colors as well as extremely thin threads through thread division. Enjoying much pursuit, appreciation, and admiration of scholars and men of letters, Gu-Style Embroidery influenced the style of embroidery in southern China.

The founder of Gu-Style Embroidery was Miao Ruiyun, one of the womenfolk of the Gu family. Withered Trees, Bamboos, and Rocks is the only real object left behind as an evidence of her embroidery art (FIG. 24).

Gu-Style Embroidery in early years was basically for family collection or given as gifts. Female embroiderers in the Gu family strive for appreciation, or it could be further viewed as pursuit of upper-class women for art attainment. In terms of embroidery art among female embroiderers in the Gu family, the most representative embroiderer was none other than Han Ximeng, grand daughter-in-law of Gu Mingshi. All her embroidered landscape, human figures, flowers, and birds were “exclusively exquisite.”

From the very beginning, Gu-Style Embroidery endeavored to imperceptibly take the lead in the concept of creation for artistic embroidery. As a result, folk embroidery started to truly form new channels for developing artistic embroidery, bringing new prospects of growth to folk embroidery lasting for over 1,000 years.

.jpg)

FIG. 23 B An Embroidered Pad of Flower Patterns Yuan Dynasty Needlework for the lotus flowers, lotus leaves, white geese, and butterflies on the surface is ordinary, except that the triangle decorative fringes around are quite special. This kind of needlework is similar to fishing-net stitch. Therefore, it is called fishing-net embroidery. This embroidered article is now preserved in the Museum of Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region.

FIG. 24 Withered Trees, Bamboos, and Rocks Ming Dynasty Gu-Style Embroidery Miao Ruiyun, a concubine of the Gu family in the Luxiang Garden, was already good at embroidery of the Song Dynasty when she was a girl. Inheriting the excellent tradition of embroidery of the Song Dynasty, she made innovation in needlework application, color-matching, and material selection. At that time, there was already the saying that “Gu-Style Embroidery started from Miao Ruiyun in Shanghai.” This embroidered article is now preserved in the Shanghai Museum.

7. A Hundred Flowers in Blossom—the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

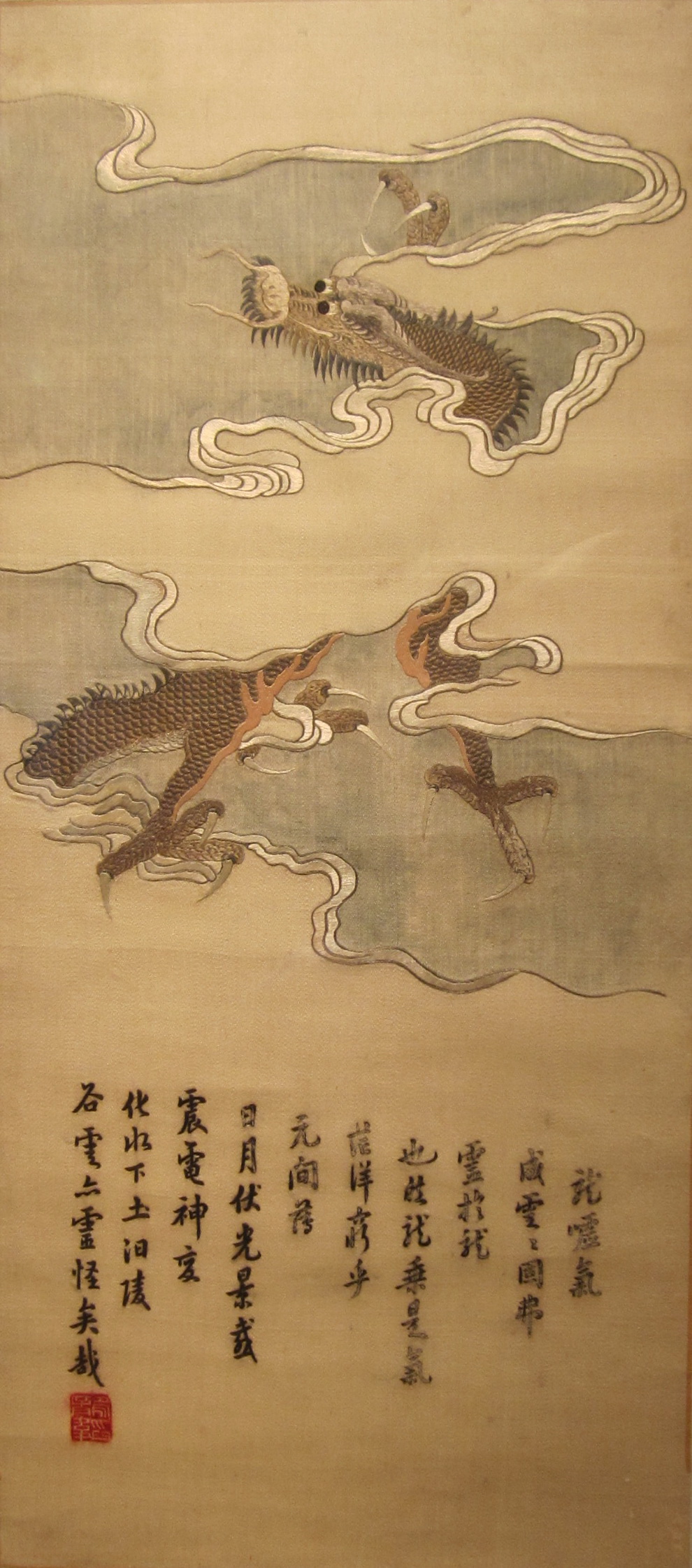

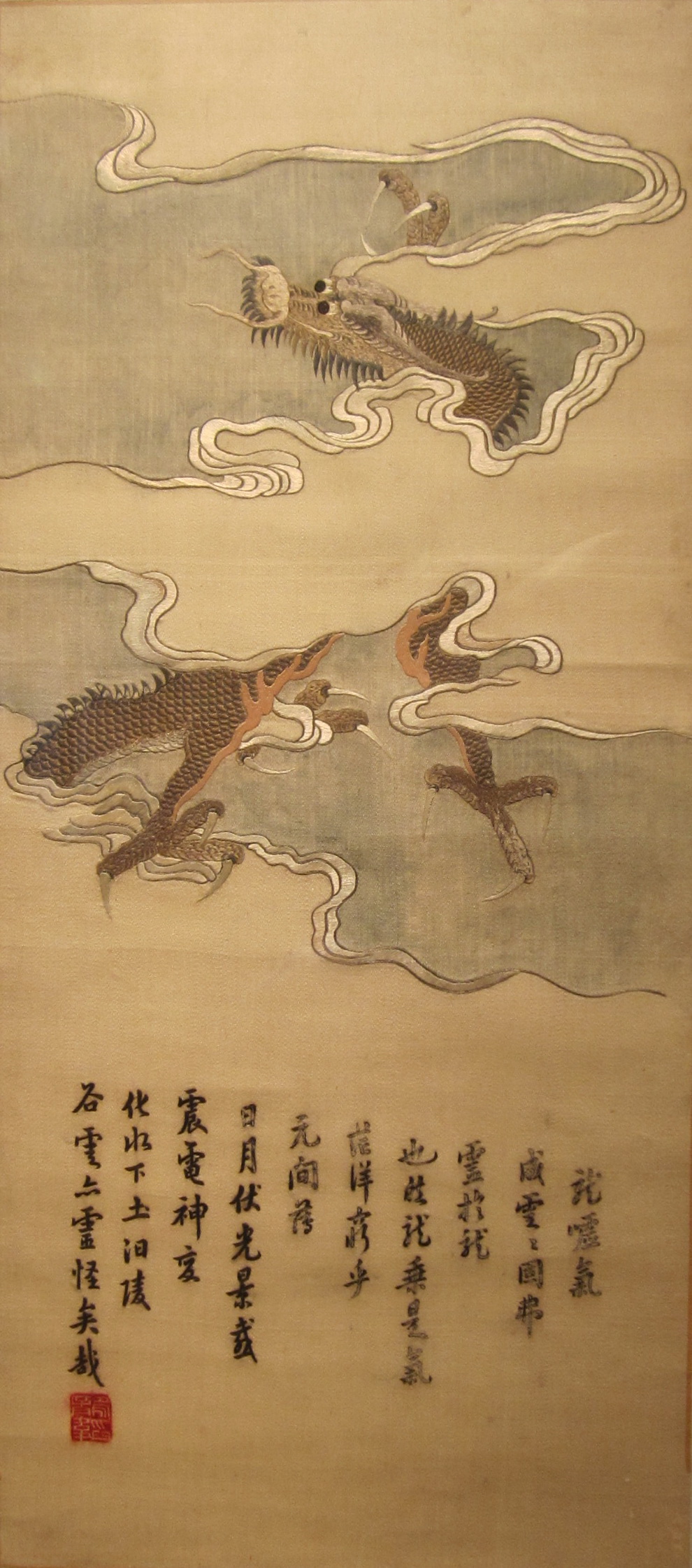

FIG. 27 Dragon by Shen Shou (1874–1921) Late Qing Dynasty Embroidery Shen Shou was first known as Yunzhi. In 1904, she embroidered eight works including a Buddha portrait and contributed them to the imperial court of the Qing Dynasty to celebrate the birthday of Empress Dowager Cixi to her great satisfaction. Cixi conferred a Chinese first name shou (longevity) on her. Later, she was sent by the Qing government to go to Japan for the exchange and research of embroidery and painting. After returning to China, she created simulation embroidery, having initiated a new style in the history of contemporary embroidery in China. This embroidered article is now preserved in the Suzhou Museum.

7. A Hundred Flowers in Blossom—the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

In the Qing Dynasty, embroidery was extensively distributed in China with a wide variety in great numbers and different styles. Moreover, official institutions got involved in management, hence leading to the maturity and development of artistic embroidery for appreciation, i.e. four major schools of embroidery gradually took shape.

Suzhou in Jiangsu Province was the center of embroidery from the middle and late Qing Dynasty. The embroidery that came from that region was known as Suzhou Embroidery (su xiu). Sichuan Embroidery (shu xiu) was produced in Chengdu in Sichuan Province. Hunan Embroidery (xiang xiu) was created in Changsha in Hunan Province. Guangzhou Embroidery (guang xiu) came from Guangzhou in Guangdong Province. Chaozhou Embroidery (chao xiu) was from Chaozhou. Guangzhou Embroidery and Chaozhou Embroidery were both called Guangdong Embroidery (yue xiu). In fact, it was not an accident that they became popular.

Let’s first take a look at Suzhou Embroidery, which is one of the four famous embroidery schools with a two-thousand-year history. As the earliest real object of Suzhou Embroidery, an embroidered coffin poll was unearthed in 1981 in Gaoyou, Jiangsu Province, from the tomb of Madame Liu, wife of Liu Xu, Guangling King from the Western Han Dynasty (about 135 BC–87 AD). This cover was embroidered by means of chain stitch needlework, presenting vivid and smooth flowing clouds, birds, animals, flowers, grass, and curved tree-branches. In the 1950s, remaining parts of embroidered Buddhist scriptures were also unearthed from under the pagoda of Yunyan Temple (built in 961) in Huqiu, Suzhou. In Suzhou in the Song Dynasty, there were such workshops of embroidery as Court-Dress Lane (gunxiu fang), Brocade Embroidery Lane (jinxiu fang), Embroidered Clothes Lane (xiuyi fang), Embroidered Flower Lane (xiuhua nong), and Embroidery Thread Lane (xiuxian xiang), etc. where embroidery works were produced. In the Ming Dynasty, Suzhou became the center of the silk industry marked by “Silkworm-breeding in every household and embroidery in every family,” basically forming a style of meticulousness, elegance, and cleanness. In the Qing Dynasty, a variety of Suzhou Embroidery and lots of embroidery shops emerged. In Suzhou alone, there were over 150 embroidery shops with more than 40,000 embroiderers (FIGS. 25, 26, 27).

The establishment of the position of the Sichuan Embroidery school as the most famous one leaves no room for doubt. The Records of the Grand Historian (Shi Ji) writes that Sichuan Province developed silk-weaving industry thanks to popular silkworm-breeding. In the Spring and Autumn Period, people in Sichuan Province were already trading their silk-woven products with present-day Thailand, which created necessary conditions for the emergence of embroidery. In the Eastern Jin Dynasty and Western Jin Dynasty, Sichuan embroidery, Shu brocade, gold, silver, gem, and jade were reputed as treasures of Sichuan. In the wake of the Tang Dynasty, there had been great demands for Sichuan embroidery among royal family members and people of all walks of life, hence making it famous across the country. In the Qing Dynasty, Sichuan Embroidery became outstanding from among those kinds of embroidery of local production. At that time, noted painters got involved with the design of the embroidery. Painters and embroiderers worked together, having constantly enhanced the art and techniques of Sichuan Embroidery. Thanks to its prosperity, Sichuan Embroidery naturally developed into one of the four famous schools in China (FIG. 28).

The formation of Hunan Embroidery was also inevitable due to its long history. In the Warring States Period, chain stitch of embroidery was frequently seen in Hunan Province. With a history of over two thousand years, it is marked by vivid patterns and meticulous craftsmanship. In the Song Dynasty and the Ming Dynasty, patterns and needlework of Hunan Embroidery became increasingly mature, quite similar to its style nowadays. In the Qing Dynasty, Hunan Embroidery was seen all over the rural and urban areas of the province, with noted embroiderers coming into being successively (FIG. 29). As pointed out by some art connoisseurs in the Qing Dynasty, Hunan Embroidery was free from the manuscripts of Chinese paintings. Instead, it underwent revision according to the needs of embroidery craftsmanship. As a result, works of Hunan Embroidery not only kept the strong points of paintings, but also gave better play to the beauty and exquisiteness of embroidery, hence having formed a unique style of art.

Guangdong Embroidery, including Guangzhou Embroidery and Chaozhou Embroidery, also has a fairly long history. Guangzhou Embroidery is fond of applying strong colors, prosperous scenes to bring about a joyful and bustling atmosphere (FIG. 30). Chaozhou Embroidery is featured by gold thread couching stitch, forming an unrestrained and bold bas-relief effect, which is different from other kinds of embroidery (FIG. 31). The craftsmanship of embroidery in Guangdong Province in the Tang Dynasty was already quite extraordinary. In the mid-Ming Dynasty, thanks to convenient transportation of costal trade in Guangdong Province, Guangdong Embroidery became world-famous. For a period of time, Guangdong-embroidered articles were reputed as “Chinese gifts for the West.” Works of Guangdong Embroidery are preserved in British, French, German, and American museums, having promoted the popularity and development of embroidery in British and French royal courts (FIGS. 32).

FIG. 25 Embroidered work A Pheasant and a White Rabbit of the Ming Dynasty preserved in the Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute.

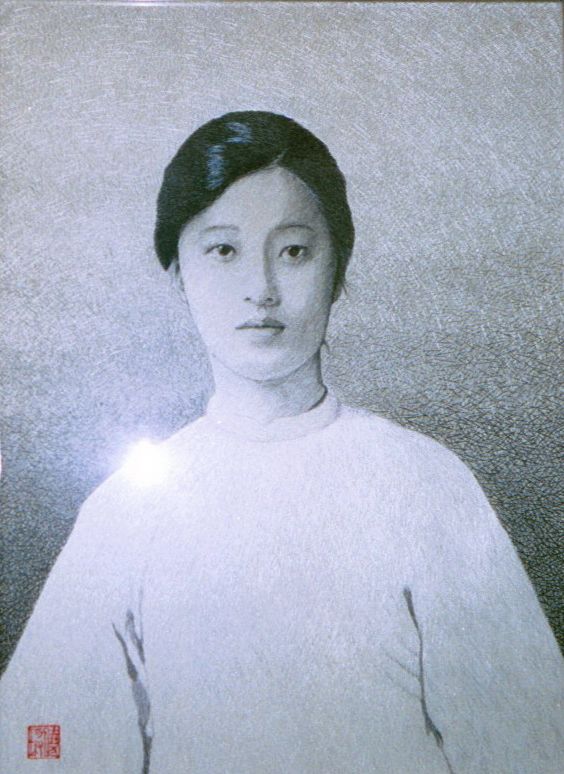

FIG. 26 B Female Figure by Shao Xiaocheng Simulation Embroidery Simulation embroidery was a new technique created by Shen Shou, an artist of Suzhou Embroidery in the late Qing Dynasty. She integrated the strong points of Western fine arts with traditional Chinese needlework to express the yin and yang layers as well as shading perspectives of photography. Her innovation became a milestone in the circle of Suzhou Embroidery in the late Qing Dynasty. This portrait was embroidered by the author through simulation embroidery. A variety of traditional Chinese needlework and embroidery technique were combined and merged with Western art of light effects. Only outlines and patchy lines are seen on the fabric, without any base of painting and color, hence appropriately revealing the youthfulness, pure beauty, plumpness, and quietness of a young girl as well as very proficiently applying the technique of simulation embroidery. This embroidered article is preserved by an individual in Taiwan.

FIG. 27 Dragon by Shen Shou (1874–1921) Late Qing Dynasty Embroidery Shen Shou was first known as Yunzhi. In 1904, she embroidered eight works including a Buddha portrait and contributed them to the imperial court of the Qing Dynasty to celebrate the birthday of Empress Dowager Cixi to her great satisfaction. Cixi conferred a Chinese first name shou (longevity) on her. Later, she was sent by the Qing government to go to Japan for the exchange and research of embroidery and painting. After returning to China, she created simulation embroidery, having initiated a new style in the history of contemporary embroidery in China. This embroidered article is now preserved in the Suzhou Museum.

FIG. 28 A frameless embroidered article named Five Children Striving for the Champion of Sichuan Embroidery of the Qing Dynasty preserved in the Museum of Sichuan Province.

FIG. 29 Lion, Deer, Elephant and Horse Embroidery on White Satin Late Qing Dynasty Hunan Embroidery of Wu Caixia’s Embroidery Workshop Museum of Hunan Province It is one of the representatives of Hunan Embroidery in early days. The establishment of Wu Caixia’s embroidery workshop was closely associated with the name of Hu Lianxian (1832–1899), the founder of Hunan Embroidery. Born in Anhui Province, Hu Lianxian later moved to settle down in Suzhou together with her father. She began to learn Suzhou Embroidery during her childhood in addition to painting, which she was very good at. After marrying, she went to live in Xiangyin of Hunan Province together with her husband. Her two sons set up Wu Caixia’s Embroidery Workshop in Changsha, which started to become famous across China.

FIG. 30 Phoenix Facing the Sun Guangzhou Embroidery With classic patterns of Guangzhou Embroidery, this embroidered article has a typical style of the region’s embroidery. It is popular among people thanks to its connotation of auspiciousness, joyful celebration, blessing, and happiness. The phoenix is encircled by birds of various postures, along with the sun, clouds, Chinese parasol, peony, magnolia, purple vine, lotus flower, and camellia in reasonable space-distribution of immense magnificence. Embroiderers of Guangzhou Embroidery are good at leaving behind water-paths (i.e. empty fringe-lines), forming a bustling scene marked by clear veins, bright colors, and distinctive layers.

FIG. 31 Dragon of Chaozhou Embroidery preserved in Beijing Shao Xiaocheng Embroidery Research Institute.

FIG. 32 Fan Cases Guangdong Embroidery It was sold for RMB 18,000 at the China Guardian Auction Block in spring, 2005.